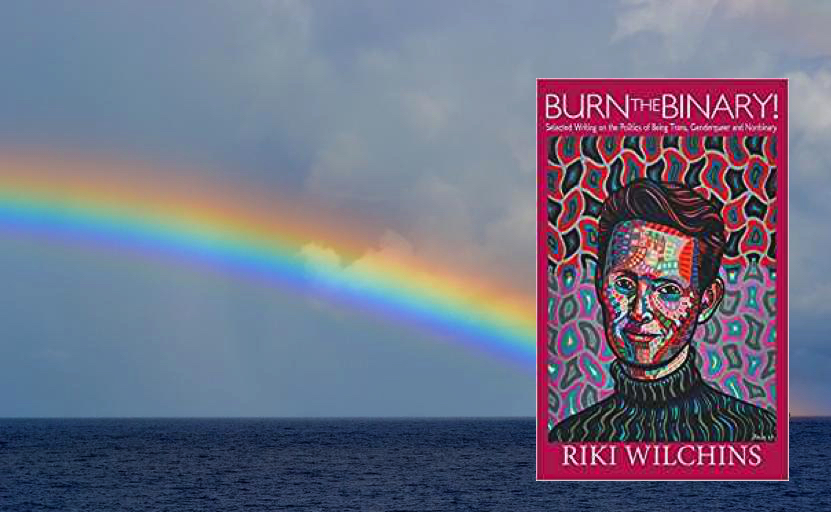

TBR Tuesday Review: Burn the Binary by Rikki Wilchins

Burn the Binary!

Selected Writings on the Politics of

Trans, Genderqueer and Nonbinary

by Riki Wilchins

From Amazon:

An icon of transgender activism for three decades, Riki Wilchins is the author of four influential books on genderqueer, trans politics, and queer theory. Riki Wilchins has been a pioneering and influential thinker and writer for a quarter of a century. Now this single volume offers a selection of Riki’s most penetrating and insightful pieces, as well as the best of two decades of Riki’s online columns for The Advocate never before collected.

5 Stars

Growing up with lesbian parents, I’m far more in-tune with old school lesbians who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s than I am with the younger generation. I have, at times, been mentally snarky towards young lesbians who corrected me on something queer or tried to educate me on what it means to be a lesbian today. I knew lesbians before they were even born. I sound old, don’t I? It’s ok. I am old.

But.

Having kids and friends with kids changes the conversations in which I regularly participate. I read a lot of middle grade books. And as someone who moves in queer circles, I read a lot of queer middle grade fiction. Probably more than most forty-five-year-olds. I feel well-versed in the young trans and nonbinary conversation, and I love the inclusion and diversity of my children’s generation.

I’ve read the most recent psychological studies about gender and article upon article written from all different perspectives—teens, parents, young adults, scholars and religious leaders. But when it comes to trans and nonbinary history and culture, my education has been lacking up till now. When I saw BURN THE BINARY on Net Galley I had to request it. The conversation about trans, genderqueer and nonbinary people may feel very new, but I wanted to know some historical context. After all, genderqueer people have always been with us, whether society chose to see them or not.

Rikki Wilchins, who is approaching my parents’ age, provides the historic perspective that I needed. Their voice is at times a war cry, as they detail their life-long fight for trans rights and visibility. One of the founding members of The Transexual Menace and GenderPAC, Wilchins has been on the front lines of the fight for gender equality for decades.

Wilchins gives us not just a course in gender issues, but context for the concept of nonbinary gender, which may be new to some readers. As one of the earliest proponents of the word, “Genderqueer,” Wilchins takes us by the hand and explains, yes, this is a valid identity, and here, look at the different ways gender can work for people, and yes, don’t we see this is common sense to be accepting of other people. But they are never impatient as they explain in different ways and from different angles how this concept works in real life.

I liked the concept of “the bathroom of least surprise,” to determine who should use which stall. Simply put, which is more surprising, someone standing at a urinal in a dress and high heels, or someone similarly dressed exiting the women’s room?

But Wilchins also writes about being a parent, and worrying about their child being bullied.

“It strikes me now that being a parent dramatically enlarges your zone of vulnerability, while at the same time shrinking your range of response.”

Their writing is tight and concise, at times angry, poignant and vulnerable the next. It contains more of historical context than other memoirs by transgender writers. It’s as if they are saying, look at us, we are here, we are beautiful, and we are deeply human. Wilchins is aware of the intersectionality of gender politics and race and doesn’t shy away from the conversation.

Wilchins writes about the evolution of language and against the “hierarchy of legitimacy” that accompanies those conversations. I could see echoes of my own queerspwan experience when they wrote about being schooled in language by youth and excluded by the Michigan Womyn Fest, which my own family was excluded from since my lesbian parents had a boy-child as well as a girl.

Wilchins introduced me to new language—the genitalization of gender, for example—as well as wrote about the anger from being forced into language, specifically the label transgender, which is not of their choosing.

Part Two of the book is more memoir than newspaper article, the vulnerability more poignant after the fierce tone of part one. This is where Wilchins lets us in to the personal behind the political. The why. Heartbreakingly for me, so much pain and rejection came at the hands of the queer community. Heart-breaking but not-surprising, sadly, because I have witnessed transphobia and trans-hatred in the queer community up close. Wilchins writes openly about the pain of their childhood and the insensitivity of their transition team at Cleveland Clinic. We see how they emerged phoenix-like in a world that actively despised them, and went on to develop that loud, clear, voice we saw in the first section. How activism healed.

“The problem is that we are trapped in a society which alternates between hating and ignoring, or toleration and exploiting us and our experience.”

Wilchins writes openly and agonizingly about their youth,

“ For the first time I learned shame: not shame for what I had or hadn’t done, but shame for what I was.”

There’re funny moments, too. For example, when they write about their name change,

“I mean, look at me, asshole. I’m a guy in a dress who gets hassled in the restroom for trying to take a pee and you’re worried that I’m going to turn out to be John Freaking Dillinger on the lam in drag?”

Wilchins writes explicitly on genitals in their many forms, but coming from a place of spreading kindness and awareness. As they explain, “The gender system, which marks kinds of bodies as either non-erotic or erotically problematic, is at work even in the most intimate spaces of our lives…Transbodies are the cracks in the gender sidewalk.” And yet, they go on to write defiantly and eloquently on the beauty of transbodies.

The reader will leave with all their questions answered—from transition to name changes to what their genitals look like or how they function. Wilchins shares it all. They makes it clear-they are not one to be pitied, nor restrained to any one container or label.

They explode the binary, deconstruct our preconceived notions of otherness. One does not gain a vagina, one loses a penis. Mankind is historically seen as an all-inclusive term, while woman is not-man. Interestingly, my own 13-year-old recently questioned me on why anyone ever thought the word “man” could ever stand in for “everyone.” I had no satisfying answer.

Wlichins owns their own story, and in deciding to share it so openly and vividly, has blazed a path for acceptance. The reader can’t look away, nor go back to what they once thought about gender.

Get a copy at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, or request a copy at your library.